2. 400037 重庆,陆军军医大学(第三军医大学)第二附属医院消化内科

2. Department of Gastroenterology, Second Affiliated Hospital, Army Medical University (Third Military Medical University), Chongqing, 400037, China

胆汁淤积(cholestasis)是多种疾病集合的常见临床综合征,病因包括肝炎、肝硬化、感染、胆道阻塞等,为胆汁形成、分泌和(或)胆汁流动障碍而造成的异常病理状态,临床上常表现为黄疸,可伴有疲劳、瘙痒、乏力等症状。早期常无特异性表现,病情进展可出现高胆红素血症,严重时可致肝功能衰竭甚至死亡。2015年曹旬旬等的流行病学调查结果显示,在4 660名慢性肝病患者中,胆汁淤积患病率为10.26% [1]。胆汁淤积时,胆汁排入肠道总量明显减少,引起肠道黏膜屏障损害,可出现内毒素及细菌移位,造成肝损伤,加重胆汁淤积。因此,凡因各种原因导致肝脏病变继而发生胆汁淤积为主要表现的肝胆疾病统称为胆汁淤积性肝病(cholestatic liver disease)。

人体内的微生物群质量约1.5 kg、微生物细胞约100万亿个[2]、微生物组基因达330万(是人类基因数量的150倍)[3],被称为人体的“主要器官”之一[4]。近年来随着研究的不断深入,揭示肠道菌群可参与介导原发性硬化性胆管炎(Primary sderosing cholangitis, PSC)、原发性胆汁性胆管炎(Primary biliary cholangitis, PBC)、肝硬化、炎症性肠病、2型糖尿病等多种疾病的发展。研究表明,肠道菌群与肝脏疾病的发生发展紧密相关。一方面,肝脏和肠道在胚胎起源上具有一致性,保有天然生理功能联系;另一方面,肠道菌群的失调可让肠内代谢产物(如肠源性毒素和微生物代谢物)经门静脉进入肝脏,通过肝-肠轴循环诱发肝细胞损伤和激活炎症免疫应答,从而导致肝功能改变。有临床研究证据表明,肠道微生物与胆汁淤积性肝病的严重程度和进展相关,PBC患者肠道中潜在的有益菌,如乳酸杆菌属和埃氏拟杆菌属明显减少,机会性致病菌如韦荣氏球菌属、链球菌属、克雷伯菌属和副流感嗜血杆菌属明显增加[5]。鉴于胆汁淤积性肝病的病因多样,目前关于肠道菌群特征在国内研究报道较少,为进一步了解该疾病肠道菌群特征,本研究收集了16例胆汁淤积性肝病患者及19例健康人群对照者的粪便样本,应用16S rRNA高通量基因测序技术探寻胆汁淤积性肝病患者和健康人群对照者的肠道菌群种类、结构和丰度差异,分析胆汁淤积性肝病与肠道菌群之间相关性,为临床诊疗提供新思路。

1 材料与方法 1.1 研究对象胆汁淤积性肝病组(病例组):收集2019年3~12月于陆军军医大学第二附属医院消化内科收治的16名患者,均符合2009年《欧洲肝病学会临床实践指南:胆汁淤积性肝病的治疗》的诊断标准。健康人群对照组:川北医学院附属医院消化内科19例无慢性疾病的健康人群。受试者及其家属对本次研究目的知情同意。排除标准:入组前14 d内曾使用抗生素、微生态制剂等;妊娠或准备妊娠的妇女及哺乳期妇女;有严重原发性疾病及精神疾病等无法配合者;不愿意参与者。

1.2 标本采集在清洁环境中采集研究对象的新鲜粪便(不少于10 g),用无菌棉签挑取新鲜粪便置于无菌采样管中送至实验室,放入-80 ℃超低温冰箱中保存待检。

1.3 DNA提取及高通量测序粪便样本使用磁珠法进行总DNA提取(粪便基因组DNA提取试剂盒,北京天根生化科技有限公司),保存于-20 ℃。粪便DNA样本终体积为50 μL,用紫外分光光度计检测浓度及纯度后,置于干冰中外送广东南芯医疗科技有限公司进行PCR扩增及16S rRNA基因V4区测序。

1.4 生物信息学分析测序得到的原始数据经过质量控制后进行序列拼接。在99%相似度下聚类得到操作分类单元(OTU)并去除嵌合体序列。菌群丰度分析运用Mann-Whitney U和Kruskal-Wallis检验,并用Benjamini-Hochberg算法校正。LEfSe分析法通过将非参数统计检验(Kruskal-Wallis多组检验和Wilcoxon秩和检验)与线性判别分析相结合。

1.5 统计学分析年龄、性别、BMI以x±s表示,数据处理和分析采用GraphPad Prism 8.0软件进行。正态分布数据的组间比较采用t检验;非正态分布数据的组间比较采用Mann-Whitney U检验。Pearson法分析肠道菌群与疾病临床参数间的相关性。P < 0.05为差异有统计学意义。

2 结果 2.1 研究对象基本概况病例组:共16名患者(男性10名、女性6名),年龄(49.1±16.5)岁,BMI (22.75±1.42)kg/m2。健康人群对照组:共19例健康人群(男性10例、女性9例),年龄(45.7±13.1)岁,BMI(22.84±2.41)kg/m2。两组性别、年龄、BMI无统计学差异(P>0.05),临床血清学指标有统计学差异(P < 0.01)。见表 1。

| 组别 | n | 男/女 | 年龄/岁 | BMI/kg·m-2 | AST/U·L-1 | ALT/U·L-1 | ALP/g·L-1 | GGT/U·L-1 | TB/μmol·L-1 | UCB/μmol·L-1 | CB/μmol·L-1 | TBA/μmol·L-1 |

| 对照组 | 19 | 10/9 | 45.7±13.1 | 22.84±2.41 | 20.3±6.3 | 22.1±8.7 | 63.5±16.8 | 28.0±10.2 | 12.0±4.6 | 8.7±4.3 | 3.3±1.0 | 7.3±6.2 |

| 病例组 | 16 | 10/6 | 49.1±16.5 | 22.75±1.42 | 183.5±187.5a | 224.0±194.2a | 360.3±247.3a | 466.5±428.0a | 232.0±100.3a | 104.3±44.1a | 127.6±63.6a | 202.6±130.5a |

| a:P < 0.01, 与对照组比较 | ||||||||||||

2.2 组间肠道菌群差异分析 2.2.1 多样性分析

从35例样本中共获得1 479 295条高质量的近全长16S rRNA序列,平均每个样品42 265条,其中病例组共得到42 424条,对照组42 131条。以99%的序列相似性聚类得到3 980 OTUs,其中病例组1 822 OTUs,对照组2 158 OTUs。α多样性反映样本内的物种多样性,采用Chao1丰度(估计真实物种数量)和Shannon指数(反映菌群多样性)表现,结果表明,病例组的Chao1与对照组比较可见明显减少趋势,但无统计学差异(P>0.05,图 1A),同时比较两组Shannon指数(图 1B)未见统计学差异(P>0.05)。β多样性反映样本间的物种多样性差异,主坐标分析(principal coordinates analysis, PCoA)为常规可视化呈现方法。分析表明,病例组和对照组间个体肠道菌群组成群落分布明显分开,具有统计学差异(P <0.01,图 1C、D)。

|

| A:Chao1丰度;B:Shannon指数;C:unweighted-UniFrac层级聚类(P < 0.01);D:weighted-nomornalised-unifrac层级聚类(P < 0.01) 图 1 组间肠道菌群多样性 |

2.2.2 菌群结构分析

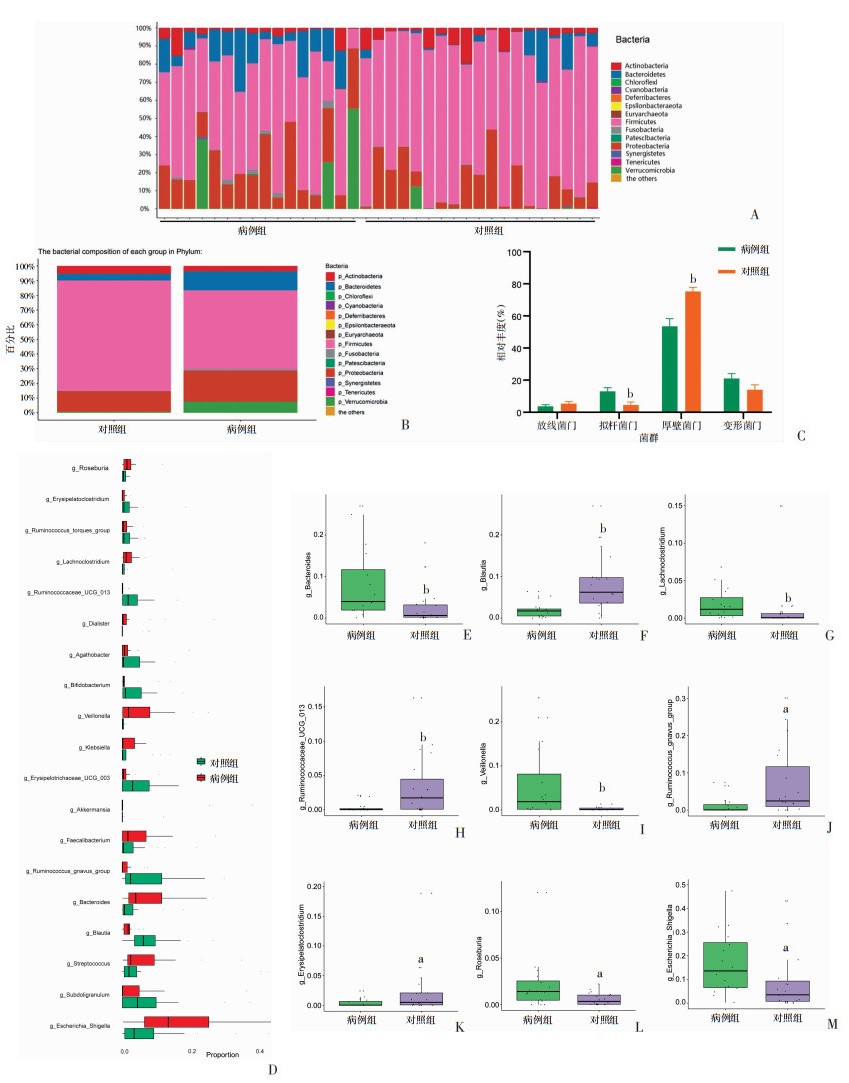

在门水平上,病例组和对照组大部分肠道菌群属于Firmicutes(厚壁菌门)、Proteobacteria(变形菌门)、Bacteroidetes(拟杆菌门)和Actinobacteria(放线菌门)。病例组与对照组的平均丰度最高分别为Firmicutes 53.6%、75.2%,Proteobacteria 21%、14%,Bacteroidetes 13%、4.5%和Actinobacteria 3.6%、5.3%。其中,Firmicutes(P < 0.01)和Bacteroidetes (P < 0.01)在两组中差异有统计学意义(图 2A~C)。在相对丰度>1%的属水平上可注释到19种细菌属(图 2D)。病例组中Bacteroides(拟杆菌属)、Lachnoclostridium、Veillonella(韦荣氏球菌属)显著高于对照组(P < 0.01),此外,Roseburia(罗斯氏菌属)、Escherichia_shigella(大肠埃希菌属-志贺氏菌属)在病例组中相对丰度高,与对照组比较具有统计学差异(P < 0.05)。Blautia(布劳特氏菌属,P < 0.01)、Ruminococcaceae_UCG_013(瘤胃菌科_UCG_013属)(P < 0.01)、Ruminococcus_gnavus_group(瘤胃球菌属_gnavus_group)和Erysipelatoclostridium在对照组中相对丰度升高,与病例组比较具有统计学差异(P < 0.05,图 2E~M)。

|

| A:门水平物种注释条形图;B、C:门水平组成分析;D:属水平上显著差异属注释分布;E~M:单个显著差异属的相对丰度分析;a:P < 0.05,b:P < 0.01,与病例组比较 图 2 组间肠道菌群组成分析 |

2.3 肠道关键菌群LEfSe分析

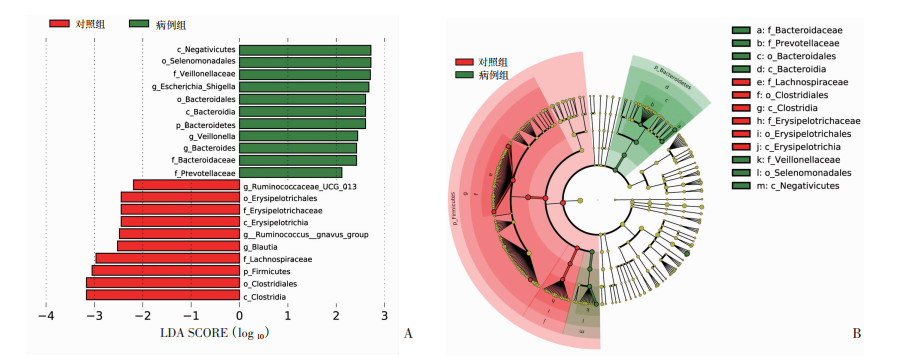

为进一步观察两组间肠道菌群的差异,我们进行LEfSe分析筛选重要菌群生物标记。将病例组与对照组肠道菌群进行比较,结果显示(图 3A、B),二组间具有显著差异的物种数量分别有11种及10种。病例组的肠道关键菌群门水平上以Bacteroidetes(拟杆菌门)为主,科水平主要集中于Veillonellaceae(韦荣氏球菌科)、Bacteroridaceae(拟杆菌科)、Prevotellaceae(普雷沃氏菌科),属水平主要集中于Escherichia_Shigella(大肠埃希菌属-志贺氏菌属)、Veillonella(韦荣氏球菌属)和Bacteroides(拟杆菌属)。对照组的肠道关键菌群门水平上以Firmicutes(厚壁菌门)为主,但科水平主要集中于Erysipelotrichaceae(丹毒丝菌科)、Lachnospiraceae(毛螺菌科),属水平主要集中于Ruminococcaceae_UCG_013(瘤胃菌科_UCG_013属)、Ruminococcus_gnavus_group(瘤胃球菌属_gnavus_group)和Blautia(布劳特氏菌属)。

|

| A:不同组间线性判别分析(LDA)效应量分布,X轴表示LDA SCORE (Log10),Y轴表示显著差异菌属(LDA SCORE>2);B:两组中具有显著差异的分类进化枝弧形图,从内而外依次表现差异菌属从属关系,节点大小对应差异菌属的平均相对丰度,红色区域为对照组差异菌属分布区域,绿色区域为病例组差异菌属分布区域 图 3 肠道菌群LEfSe分析 |

2.4 肠道菌群与临床参数间相关性分析

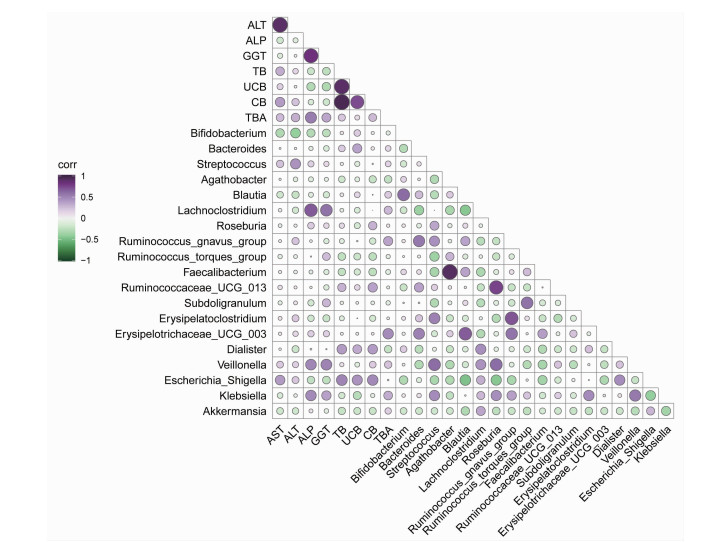

为探求属水平上显著差异菌属是否与临床血清学指标具有相关性,本文对胆汁淤积性肝病患者肠道菌群与临床血清学指标进一步完成了Pearson相关系数分析,结果如图 4所示,Lachnoclostridium与ALP(P < 0.01)、GGT(P < 0.05)强相关。Veillonella(韦荣氏菌属)与GGT强相关(P < 0.05)。此外,结果显示,Ruminococcus_gnavus_group和Erysipelotrichaceae_UCG_003与Bacteroides强相关(P < 0.05),Bifidobacterium(双歧杆菌)与ALT弱相关;Roseburia与Ruminococcaceae_UCG_013 (P < 0.05)及Veillonella(韦荣氏球菌属)(P < 0.05)强相关。Faecalibacterium(粪杆菌)与Agathobacter强相关(P < 0.001)。

|

| 紫色代表正相关,绿色代表负相关;圆圈大小表示相关性,圆圈越大代表相关性数值越高 图 4 肠道菌群与临床参数间的相关性 |

3 讨论

在人体中,胃肠道代表了一个庞大的微生物生态系统,容纳了百万亿个微生物细胞[6]。研究表明,肠道菌群在宿主中发挥着重要作用[7],如保护机体防止病原体过度生长[8]、影响宿主细胞的增殖[9]和血管化[10]、调节肠道内分泌功能[11]、参与神经系统信号传导[12]及影响骨密度[13]、为能量生成提供来源[14](占宿主每日能量需求量的5%~10%)、参与维生素[15]和神经递质[12]的合成、代谢胆汁盐[16]、参与代谢及调节特定药物和消除外源性毒素[17]。因此,人体肠道中的菌群与宿主之间构成了一个庞大的有机网络[18]。

本研究中,我们采用16s rRNA高通量测序方法检测了胆汁淤积性肝病组和健康人群对照组的肠道菌群,共得到了1 479 295条序列,聚类成3 980 OTUs,由13个门、80个科、273个属组成,组间Chao1和Shannon指数明显减少,无统计学差异(P>0.05),β多样性反映组间物种多样性有统计学差异(P < 0.01)。PcoA分析显示,两组菌群大部分属于Firmicutes(厚壁菌门)、Bacteroidetes(拟杆菌门)、Proteobacteria(变形菌门)和Actinobacteria(放线菌门),与健康人群对照组肠道菌群门水平结构相比,胆汁淤积性肝病组中Bacteroidetes(厚壁菌门)、Proteobacteria(变形菌门)和Verrucomicrobia(疣微菌门)的占比更大。研究显示,厚壁菌门/拟杆菌门的比值可作为评估人类肠道病理状况的潜在生物学指标[19],疾病状态下,厚壁菌门/拟杆菌门比值多为升高[20],但在最近的研究报道中,表明厚壁菌门/拟杆菌门比值高低与ICU中患者的并发症和存活率之间并无关联,当厚壁菌门和拟杆菌门的相对丰度都升高时,比值反而下降[21]。值得注意的是,Lachnoclostridium在胆汁淤积性肝病组中明显富集,既往文献报道,在诊断大肠腺瘤的预测分析上,Lachnoclostridium可作为非侵入性诊断标记物[22],本研究中Lachnoclostridium相对丰度相较于健康人群对照组为优势菌属,结合Pearson相关性分析结果,Lachnoclostridium的高丰度表达与ALP(P < 0.01)、GGT(P < 0.05)强相关。

LEfSe分析表明,胆汁淤积性肝病组中Bacteroides(拟杆菌属)、Veillonella、Escherichia_shigella占绝对优势,健康人群组以Blautia(布劳特氏菌属)、Ruminococcus_gnavus_group及Ruminococcaceae_UCG_013为优势菌属。文献报道,Ruminococcaceae(厚壁菌门家族成员之一,专性厌氧菌)为正常肠道菌群组成之一[23-24],Blautia具有益生菌作用,能在体内产生高浓度乙酸以加强肠上皮细胞紧密连接,阻止病原菌感染[25],并且在结肠癌[26]、肝硬化[27]中有改善预后作用,对造血干细胞移植术后患者发生移植物抗宿主导致相关的死亡也可起到保护作用[28]。除此之外,Blautia还可参与短链脂肪酸(Short chain fatty acids,SCFA)合成,已知SCFA是强效抗炎物质,参与介导免疫反应诱导调节性T细胞形成, 是宿主和结肠上皮的重要来源[29-30]。Bacteroides的丰度升高可引发炎症效应,介导胰岛素抵抗、肥胖等疾病发展[31-33]。研究发现,Veillonella在肺癌中丰度明显升高,Megasphaera(巨球型菌属)和Veillonella的结合在肺癌预测模型中具有高AUC值[34-35],与克罗恩病并发症[36]、以TNF-α、IL-1β降低及CCL2、CCL17升高为主的儿童哮喘也相关[37]。在PSC治疗中,熊去氧胆酸反应充分者在治疗后Veillonella丰度减少,而反应欠佳的患者在熊去氧胆酸治疗期间Veillonella增加,我们的研究也表明Veillonella与GGT强相关(P < 0.01),这提示着Veillonella的相对高丰度或许可作为诊断胆汁淤积性肝病的潜在生物标记点,但具体机制还需进一步研究。因Escherichia_shigella和Klebsiella为临床常见条件性致病菌[38],自然在稳态失衡环境中明显升高,成为胆汁淤积性肝病的优势菌属之一,相关性分析表明,Klebsiella和Veillonella强相关(P < 0.05),因此,抑制Veillonella的丰度表达或可成为治疗该疾病的潜在靶点。

当然,本研究也存在一定的局限性,未将治疗前后肠道菌群进行纵向比对,无法呈现疾病状态下肠道菌群动态改变特征。总体而言,本文分析了胆汁淤积性肝病患者与健康人群对照者的肠道菌群多样性及结构组成,并将肠道菌群差异菌属与胆汁淤积性肝病患者的临床血清学指标进行了相关性分析。综上,胆汁淤积性肝病患者与健康人群对照者相比,肠道菌群存在特征性改变,但具体机制还需进一步研究。因此在后续研究中,我们将专注动物模型研究等方法对此次结果加以验证,为临床诊疗提供新思路。

| [1] |

曹旬旬, 高月求, 张文宏, 等. 基于上海市住院慢性肝病患者胆汁淤积患病率的调查研究[J]. 中华肝脏病杂志, 2015, 23(08): 569-573. CAO X X, GAO Y Q, ZHANG W H, et al. Cholestasis morbidity rate in first-hospitalized patients with chronic liver disease in Shanghai[J]. Chin J Hepato, 2015, 23(8): 569-573. DOI:10.3760/cma.j.issn.1007-3418.2015.08.003 |

| [2] |

PFLUGHOEFT K J, VERSALOVIC J. Human microbiome in health and disease[J]. Annu Rev Pathol Mech Dis, 2012, 7(1): 99-122. DOI:10.1146/annurev-pathol-011811-132421 |

| [3] |

QIN J J, LI R Q, RAES J, et al. A human gut microbial gene catalogue established by metagenomic sequencing[J]. Nature, 2010, 464(7285): 59-65. DOI:10.1038/nature08821 |

| [4] |

VELMURUGAN G, DINAKARAN V, RAJENDHRAN J, et al. Blood microbiota and circulating microbial metabolites in diabetes and cardiovascular disease[J]. Trends Endocrinol Metab, 2020. DOI:10.1016/j.tem.2020.01.013 |

| [5] |

KUMMEN M, HOV J R. The gut microbial influence on cholestatic liver disease[J]. Liver Int, 2019, 39(7): 1186-1196. DOI:10.1111/liv.14153 |

| [6] |

LYNCH S V, PEDERSEN O. The human intestinal microbiome in health and disease[J]. N Engl J Med, 2016, 375(24): 2369-2379. DOI:10.1056/NEJMra1600266 |

| [7] |

FULDE M, HORNEF M W. Maturation of the enteric mucosal innate immune system during the postnatal period[J]. Immunol Rev, 2014, 260(1): 21-34. DOI:10.1111/imr.12190 |

| [8] |

KAMADA N, CHEN G Y, INOHARA N, et al. Control of pathogens and pathobionts by the gut microbiota[J]. Nat Immunol, 2013, 14(7): 685-690. DOI:10.1038/ni.2608 |

| [9] |

IJSSENNAGGER N, BELZER C, HOOIVELD G J, et al. Gut microbiota facilitates dietary heme-induced epithelial hyperproliferation by opening the mucus barrier in colon[J]. Proc Natl Acad Sci, 2015, 112(32): 10038-10043. DOI:10.1073/pnas.1507645112 |

| [10] |

REINHARDT C, BERGENTALL M, GREINER T U, et al. Tissue factor and PAR1 promote microbiota-induced intestinal vascular remodelling[J]. Nature, 2012, 483(7391): 627-631. DOI:10.1038/nature10893 |

| [11] |

NEUMAN H, DEBELIUS J W, KNIGHT R, et al. Microbial endocrinology: the interplay between the microbiota and the endocrine system[J]. FEMS Microbiol Rev, 2015, 39(4): 509-521. DOI:10.1093/femsre/fuu010 |

| [12] |

YANO J M, YU K, DONALDSON G P, et al. Indigenous bacteria from the gut microbiota regulate host serotonin biosynthesis[J]. Cell, 2015, 161(2): 264-276. DOI:10.1016/j.cell.2015.02.047 |

| [13] |

CHO I, YAMANISHI S, COX L, et al. Antibiotics in early life alter the murine colonic microbiome and adiposity[J]. Nature, 2012, 488(7413): 621-626. DOI:10.1038/nature11400 |

| [14] |

CANFORA E E, JOCKEN J W, BLAAK E E. Short-chain fatty acids in control of body weight and insulin sensitivity[J]. Nat Rev Endocrinol, 2015, 11(10): 577-591. DOI:10.1038/nrendo.2015.128 |

| [15] |

YATSUNENKO T, REY F E, MANARY M J, et al. Human gut microbiome viewed across age and geography[J]. Nature, 2012, 486(7402): 222-227. DOI:10.1038/nature11053 |

| [16] |

DEVLIN A S, FISCHBACH M A. A biosynthetic pathway for a prominent class of microbiota-derived bile acids[J]. Nat Chem Biol, 2015, 11(9): 685-690. DOI:10.1038/nchembio.1864 |

| [17] |

HAISER H J, GOOTENBERG D B, CHATMAN K, et al. Predicting and manipulating cardiac drug inactivation by the human gut bacterium Eggerthella lenta[J]. Science, 2013, 341(6143): 295-298. DOI:10.1126/science.1235872 |

| [18] |

GUO Y J, YANG X F, QI Y E, et al. Long-term use of ceftriaxone sodium induced changes in gut microbiota and immune system[J]. Sci Rep, 2017, 7: 43035. DOI:10.1038/srep43035 |

| [19] |

LEY R E, TURNBAUGH P J, KLEIN S, et al. Microbial ecology: human gut microbes associated with obesity[J]. Nature, 2006, 444(7122): 1022-1023. DOI:10.1038/4441022a |

| [20] |

COSORICH I, DALLA-COSTA G, SORINI C, et al. High frequency of intestinal TH17 cells correlates with microbiota alterations and disease activity in multiple sclerosis[J]. Sci Adv, 2017, 3(7): e1700492. DOI:10.1126/sciadv.1700492 |

| [21] |

LANKELMA J M, VUGHT L A, BELZER C, et al. Critically ill patients demonstrate large interpersonal variation in intestinal microbiota dysregulation: a pilot study[J]. Intens Care Med, 2017, 43(1): 59-68. DOI:10.1007/s00134-016-4613-z |

| [22] |

LIANG J Q, LI T, NAKATSU G, et al. A novel faecal Lachnoclostridium marker for the non-invasive diagnosis of colorectal adenoma and cancer[J]. Gut, 2020, 69(7): 1248-1257. DOI:10.1136/gutjnl-2019-318532 |

| [23] |

NAVA G M, FRIEDRICHSEN H J, STAPPENBECK T S. Spatial organization of intestinal microbiota in the mouse ascending colon[J]. ISME J, 2011, 5(4): 627-638. DOI:10.1038/ismej.2010.161 |

| [24] |

SHOGAN B D, SMITH D P, CHRISTLEY S, et al. Intestinal anastomotic injury alters spatially defined microbiome composition and function[J]. Microbiome, 2014, 2(1): 1-10. DOI:10.1186/2049-2618-2-35 |

| [25] |

FUKUDA S, TOH H, HASE K, et al. Bifidobacteria can protect from enteropathogenic infection through production of acetate[J]. Nature, 2011, 469(7331): 543-547. DOI:10.1038/nature09646 |

| [26] |

CHEN W G, LIU F L, LING Z X, et al. Human intestinal lumen and mucosa-associated microbiota in patients with colorectal cancer[J]. PLoS ONE, 2012, 7(6): e39743. DOI:10.1371/journal.pone.0039743 |

| [27] |

BAJAJ J S, HYLEMON P B, RIDLON J M, et al. Colonic mucosal microbiome differs from stool microbiome in cirrhosis and hepatic encephalopathy and is linked to cognition and inflammation[J]. Am J Physiol-Gastrointest Liver Physiol, 2012, 303(6): G675-G685. DOI:10.1152/ajpgi.00152.2012 |

| [28] |

JENQ R R, TAUR Y, DEVLIN S M, et al. Intestinal Blautia is associated with reduced death from graft-versus-host disease[J]. Biol Blood Marrow Transplant, 2015, 21(8): 1373-1383. DOI:10.1016/j.bbmt.2015.04.016 |

| [29] |

ZHANG J C, GUO Z, XUE Z S, et al. A Phylo-functional core of gut microbiota in healthy young Chinese cohorts across lifestyles, geography and ethnicities[J]. ISME J, 2015, 9(9): 1979-1990. DOI:10.1038/ismej.2015.11 |

| [30] |

ROOKS M G, GARRETT W S. Gut microbiota, metabolites and host immunity[J]. Nat Rev Immunol, 2016, 16(6): 341-352. DOI:10.1038/nri.2016.42 |

| [31] |

GRASSET E, PUEL A, CHARPENTIER J, et al. A specific gut microbiota dysbiosis of type 2 diabetic mice induces GLP-1 resistance through an enteric NO-dependent and gut-brain axis mechanism[J]. Cell Metab, 2017, 25(5): 1075-1090. DOI:10.1016/j.cmet.2017.04.013 |

| [32] |

FARIA GHETTI F, OLIVEIRA D G, OLIVEIRA J M, et al. Influence of gut microbiota on the development and progression of nonalcoholic steatohepatitis[J]. Eur J Nutr, 2018, 57(3): 861-876. DOI:10.1007/s00394-017-1524-x |

| [33] |

LIEBER A D, BEIER U H, XIAO H Y, et al. Loss of HDAC6 alters gut microbiota and worsens obesity[J]. FASEB J, 2019, 33(1): 1098-1109. DOI:10.1096/fj.201701586R |

| [34] |

YAN X M, YANG M X, LIU J, et al. Discovery and validation of potential bacterial biomarkers for lung cancer[J]. Am J Cancer Res, 2015, 5(10): 3111-3122. |

| [35] |

LEE S, SUNG J Y, YONG D, et al. Characterization of micro-biome in bronchoalveolar lavage fluid of patients with lung cancer comparing with benign mass like lesions[J]. Lung Cancer, 2016, 102: 89-95. DOI:10.1016/j.lungcan.2016.10.016 |

| [36] |

KUGATHASAN S, DENSON L A, WALTERS T D, et al. Prediction of complicated disease course for children newly diagnosed with Crohn's disease: a multicentre inception cohort study[J]. Lancet, 2017, 389(10080): 1710-1718. DOI:10.1016/S0140-6736(17)30317-3 |

| [37] |

THORSEN J, RASMUSSEN M A, WAAGE J, et al. Infant airway microbiota and topical immune perturbations in the origins of childhood asthma[J]. Nat Commun, 2019, 10(1): 5001. DOI:10.1038/s41467-019-12989-7 |

| [38] |

SHEN F, ZHENG R D, SUN X Q, et al. Gut microbiota dysbiosis in patients with non-alcoholic fatty liver disease[J]. Hepatobiliary Pancreat Dis Int, 2017, 16(4): 375-381. DOI:10.1016/S1499-3872(17)60019-5 |