2. 830000 乌鲁木齐,兰州军区乌鲁木齐总医院临床检验中心

2. Clinical Laboratory Diagnostic Center, Urumqi General Hospital of Lanzhou Military Command, Urumqi, Xinjiang Uygur Autonomous Region, 830000, China

金黄色葡萄球菌(Staphylococcus aureus),简称金葡菌,是一种重要的人类机会致病菌,常引起皮肤、软组织感染,关节、骨感染,心内膜炎、败血症以及中毒性休克等多种疾病,病死率高[1]。明确特定区域的金葡菌主要流行克隆、切断其传播途径、终止耐药菌株在人群中传播是控制金葡菌流行的重要策略,故检测金葡菌流行菌株的分子特征及耐药谱对控制金葡菌感染有重要意义。

按菌株耐药性的差异,金葡菌通常被分为耐甲氧西林金葡菌(methicillin-resistant S. aureus,MRSA)和甲氧西林敏感金葡菌(methicillin-susceptible S. aureus,MSSA),其区别在于前者染色体中携带一葡萄球菌盒式染色体(staphylococcal cassette chromosome mec,SCCmec),其中的耐药基因mecA可编码对甲氧西林等β-内酰胺类抗生素耐药的决定簇,介导MRSA的耐药性。多种分子分型技术,如脉冲场凝胶电泳(PFGE),多位点序列分析(MLST),葡萄球菌A蛋白(spa)基因分型以及附属基因调节子(agr)分型等已被广泛应用于MRSA的进化和流行病学研究[2, 3, 4, 5]。研究证实,ST5,ST239和ST8是世界范围内流行的主要MRSA克隆群[6]。在我国,MRSA分离率虽因地区不同而有较大差异,总体上约占金葡菌感染的60%左右,ST239和ST5也是我国MRSA优势流行克隆[7, 8];MSSA在我国占金葡菌感染的40%左右,但目前对MSSA的研究报道非常有限,相对于MRSA而言,通常认为MSSA不存在优势克隆,而表现出更高的遗传多样性及更高的毒力因子表达[9, 10],并且与菌血症、心内膜炎以及败血症关联更密切[11]。葡萄球菌杀白细胞毒素(Panton-Valentine leucocidin,PVL)是由lukS、lukF两个基因编码的双组份细胞成孔毒素,可破坏中性粒细胞、单核细胞和巨噬细胞等免疫细胞,在金葡菌感染过程中起重要作用,也是评价金葡菌毒力的常用指标之一[12, 13, 14]。

自1961年发现MRSA以来,耐药金葡菌感染一直倍受关注[3, 5]。分子流行病学研究表明,MRSA菌通常携带较多的耐药基因,毒力较弱,常引起医院内感染;而MSSA菌携带的耐药基因较少,毒力较强,常引起社区人群感染[6, 7]。在本研究中,我们运用多种金葡菌分子分型方法,结合pvl毒力基因检测和耐药谱分析,对2010年6月至2012年12月从乌鲁木齐地区分离的86株金葡菌进行了分析研究,不仅从一定程度上揭示了我国西北地区金葡菌的流行特征,而且可为我国其他地区金葡菌感染和流行的检测提供借鉴。

1 材料与方法 1.1 材料 1.1.1 菌株来源86株金葡菌分离自乌鲁木齐地 区的一所综合教学医院,主要源自2010年 6月至2012年12月期间86位住院患者的分泌物、痰液、血液、脓等标本。其分离的标本类型和科室来源见表 1。

| 科室 | 菌株总数 (MRSA菌株数/ MSSA菌株数) | 标本类型及标本数 | |||

| 分泌物 标本数 | 痰液 标本数 | 血液 标本数 | 其他 标本数 | ||

| 骨科 | 12(5/7) | 12 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 烧伤整形科 | 10(10/0) | 9 | 0 | 0 | 1 |

| 神经外科 | 3(2/1) | 0 | 3 | 0 | 0 |

| 耳鼻喉科 | 5(1/4) | 5 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 颌面外科 | 5(0/5) | 4 | 0 | 0 | 1 |

| 创伤科 | 4(1/3) | 2 | 1 | 0 | 1 |

| 泌尿外科 | 1(0/1) | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 |

| 普外科 | 2(1/1) | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 |

| 急诊科 | 2(1/1) | 0 | 2 | 0 | 0 |

| ICU | 3(2/1) | 0 | 2 | 0 | 1 |

| 血液科 | 3(0/3) | 1 | 2 | 0 | 0 |

| 肿瘤科 | 3(0/3) | 0 | 2 | 1 | 0 |

| 呼吸内科 | 4(2/2) | 0 | 3 | 1 | 0 |

| 消化内科 | 1(0/1) | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 |

| 神经内科 | 2(1/1) | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 |

| 心血管内科 | 1(0/1) | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 |

| 中医科 | 2(0/2) | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 |

| 肾病科 | 1(0/1) | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 |

| 干部科 | 6(2/4) | 2 | 2 | 1 | 1 |

| 儿科 | 4(0/4) | 0 | 4 | 0 | 0 |

| 综合科 | 1(0/1) | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 门诊 | 11(3/8) | 8 | 3 | 0 | 0 |

| 合计 | 86(31/55) | 47 | 26 | 4 | 9 |

Bio-Rad PCR仪,Bio-Rad垂直电泳仪,Bio-Rad凝胶成像仪,Bio-Rad凝胶脉冲场电泳仪,Bio-Fosum微生物鉴定药敏分析仪(上海复星佰珞公司); OXOID Tryptone Soya Broth(TSB)培养基。

1.1.3 引物分子分型及毒力、耐药基因检测引物均参照文献设计[15, 16, 17, 18, 19, 20, 21, 22],由华大基因合成。

1.2 方法 1.2.1 细菌培养、基因组制备及菌株鉴定细菌的分离培养按《全国临床检验操作规程》进行,按照文献所述方法提取基因组DNA[23]。金葡菌及MRSA、MSSA的鉴定参照文献[24]所述,通过PCR方法检测金葡菌分离菌株的mecA与femB基因。若femB基因为阳性,mecA基因为阴性则判断为MSSA菌株;若mecA与femB基因皆为阳性,则判断为MRSA菌株。

1.2.2 MRSA菌株的SCCmec分型根据文献[16]所述方法,应用5对特异性引物通过PCR方法扩增MRSA菌株基因组,对菌株进行Ⅰ、Ⅱ、Ⅲ、Ⅳ和Ⅴ型的SCCmec分型,未扩增出特异性条带或者扩增出条带不符合判定标准的判定为未定型别(nontypable,NT)。

1.2.3 spa分型用特异性引物通过PCR扩增出金葡菌spa基因的X区[17, 25],PCR产物送上海英俊生物技术服务公司测序,将获得的序列提交spa基因分型数据库(http://www.ridom.de/spaserver),参照已公布的重复序列,根据重复序列出现的次数和排列方式确定spa型别[26]。

1.2.4 MLST分型采用PCR的方法分别扩增金葡菌7个看家基因(arcc、aroe、glp、gmk、pta、tpi、yqil)序列,产物送上海英俊生物技术服务公司测序,所获序列提交MLST数据库(http://saureus.mlst.net/)进行分析得出其MLST型别,即序列型(sequence type,ST)[15]。因MSSA菌株存在遗传多样性,定义所占比例5%以上的ST型为主要流行型别,spa主要流行型别同样如此定义。

1.2.5 MSSA菌株的agr分型参照文献[19]所述方法,通过多重PCR扩增MSSA菌株基因组,PCR产物进行电泳,441、575、323和 659 bp大小的条带分别代表agr Ⅰ型、Ⅱ型、Ⅲ型、和Ⅳ型。

1.2.6 脉冲场凝胶电泳(PFGE)分析按照文献[27]所述,将新鲜培养的金葡菌包埋于1%低熔点琼脂中,然后用溶葡萄球菌素及溶菌酶进行破壁,蛋白酶K消化,最后经限制性内切酶SmaⅠ酶切后制胶电泳。结果用软件BioNumerics version 6.6 (Applied Maths) 进行聚类分析,将同源性超过90%者定义为同一型。

1.2.7 pvl毒力基因及耐药基因检测通过PCR方法,分别用特异性引物扩增所有金葡菌的pvl基因[21],以及MSSA菌株的青霉素耐药基因blaZ和红霉素、克林霉素耐药基因ermA、ermC[20, 22],PCR产物经电泳进行判断。

1.2.8 药敏实验菌株的耐药情况用Bio-Fosum微生物鉴定药敏分析仪(上海复星佰珞公司)进行测定,按照美国临床实验室标准化协会(CLSI) 2011出版的琼脂稀释法药敏实验解释标准判断菌株对抗生素的耐药状态[28],以耐药(R)和敏感(S)表示。按照文献[29],某株金葡菌如果对至少三类抗生素耐药(每类抗生素中至少有一种代表药物耐药),则定义该菌株为多重耐药(multidrug-resistant,MDR)菌株。

2 结果 2.1 MRSA与MSSA鉴定86株临床金葡菌经PCR扩增mecA和femB基因检出MRSA菌株31株,占36.0%,MSSA菌株55株,占64.0%。

2.2 分子分型 2.2.1 MRSA菌株的SCCmec分型31株MRSA菌株经多重PCR扩增,检出SCCmec Ⅲ型25株(80.6% ),SCCmecⅤ型4株(12.9%),SCCmecⅠ型1株(3.2%),未分型1株(3.2%)。见表 2。

| 菌株类型 (菌株数) |

MLST型别 (菌株数) |

spa型别 (菌株数) |

SCC

mec型别 (菌株数) |

agr型别 (菌株数) |

pvl+菌株数 |

| MRSA(31) | ST239(22) | t030(22) | Ⅲ(22) | — | 10 |

| ST5(2) | t002(2) | Ⅲ(2) | — | 0 | |

| ST188(2) | t189(2) | Ⅴ(2) | — | 1 | |

| ST22(1) | t11413(1) | Ⅴ(1) | — | 1 | |

| ST59(1) | t437(1) | Ⅴ(1) | — | 0 | |

| ST217(1) | t3668(1) | Ⅰ(1) | — | 0 | |

| ST398(1) | t034(1) | Ⅲ(1) | — | 0 | |

| new(1) | t2592(1) | 未分型 | — | 0 | |

| MSSA(55) | ST22(12) | t11413(9),t571(1),t284(1),new(1) | — | Ⅰ(12) | 10 |

| ST121(10) | t284(3),t030(2),t159(2),t435(2),t850(1) | — | Ⅳ(8),Ⅰ(2) | 8 | |

| ST88(5) | t2592(5) | — | Ⅲ(5) | 3 | |

| ST15(5) | t002(1),t571(1),t2325(1),t11518(1),new(1) | — | Ⅱ(5) | 0 | |

| ST398(4) | t571(2),t030(1),t2876(1) | — | Ⅰ(4) | 1 | |

| ST1920(3) | t5356(2),t030(1) | — | Ⅲ(2) ,Ⅰ(1) | 0 | |

| ST217(2) | t571(1),t11413(1) | — | Ⅰ(2) | 0 | |

| ST5(2) | t002(2) | — | Ⅱ(2) | 1 | |

| ST59(2) | t163(1),t172(1) | — | Ⅰ(2) | 0 | |

| ST630(2) | t377(2) | — | Ⅰ(2) | 0 | |

| ST7(2) | t2663(1),t6193(1) | — | Ⅰ(2) | 1 | |

| ST97(2) | t267(1),t359(1) | — | Ⅰ(2) | 1 | |

| ST1(1) | t127(1) | — | Ⅲ(1) | 1 | |

| ST188(1) | t030(1) | — | Ⅰ(1) | 0 | |

| ST30(1) | t1130(1) | — | Ⅲ(1) | 1 | |

| ST943(1) | t2617(1) | — | Ⅰ(1) | 0 |

对扩增产物的测序结果进行分析,86株金葡菌株可分为31种spa基因型(表 2)。其中31株MRSA分为8种spa基因型,优势型别为t030(71.0%,22/31);55株MSSA分为23种spa基因型,主要型别有t11413(18.2%,10/55),t571(9.1%,5/55),t030(9.1%,5/55),t2592(9.1%,5/55),t284(7.3%,4/55),t002(5.5%,3/55)。另外有两株MSSA菌株未能分型,可能为新的spa型别。

2.2.3 MLST分型86株金葡菌可分为23种ST型(表 2)。在31株MRSA中,优势型别为ST239(71.0%,22/31),且均为spa t030型,另外发现6种ST型和1种新的ST型;55株MSSA分为16种ST型,主要型别有ST22(21.8%,12/55),ST121(18.2%,10/55),ST88(9.1%,5/55),ST15(9.1%,5/55),ST398(7.3%,4/55)和ST1920(5.5%,3/55)。

2.2.4 agr分型将55株MSSA菌株进行agr分型,agrⅠ占56.4% (31/55),agrⅡ占12.7%(7/55),agrⅢ占16.4%(9/55),agr Ⅳ为14.5%(8/55)。7株agrⅡ型菌株有5株为ST15型,2株为ST5型;8株agr Ⅳ菌株均为ST121型。

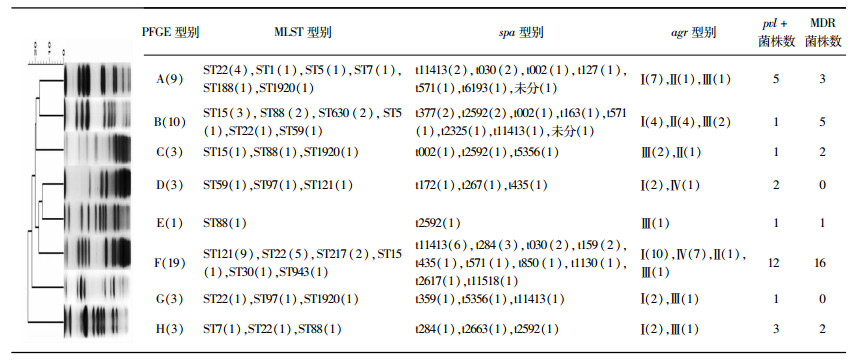

2.2.5 PFGE分型MSSA菌株基因组DNA经SmaⅠ酶切后,DNA大片段可得到很好的分离,聚类分析表明55株MSSA菌株可分为8个聚类组,依次命名为A~H型,见图 1。其中F型,B型,A型为优势型别,分别占34.5% (19/55),18.2% (10/55),和16.4% (9/55)。此外,4株ST398菌株未能分型,可能因为这些菌株的基因组存在DNA甲基化而导致不能被SmaⅠ酶切和分离[30]。

|

|

图 1 51株MSSA菌株的分子分型结果及其多重耐药菌检出情况 (除去4株PFGE未分型菌株,括号内数字为菌株数) |

31株MRSA菌株中,pvl毒力基因检出率为38.7%(12/31),12株pvl阳性菌株中有10株为ST239型,表明乌鲁木齐地区主要流行克隆ST239有较高的pvl毒力基因携带率(45.5%,10/22); 55株MSSA菌株中有27株为pvl阳性(49.1%),其中ST121型有8株,ST22型有10株(表 2),可见MSSA菌株中,ST121(80.0%,8/10)和ST22(83.3%,10/12)有较高的pvl毒力基因携带率。

2.3 药敏实验分析86株金葡菌对13种抗生素的药敏实验结果见表 3。MRSA对糖肽类抗生素(万古霉素、替考拉宁)全部敏感,仅有1株菌株对利奈唑胺耐药,2株对复方新诺明耐药,但是对其余被检抗生素的耐药率则较高(表 3)。相对于MRSA菌株而言,MSSA菌株对大多数抗生素敏感,但是对复方新诺明的耐药率(18.2%,10/55)高于MRSA菌株(6.5%,2/31)。此外,MSSA菌株主要对青霉素、红霉素、克林霉素3种抗生素耐药,耐药率分别为89.1%(49/55),67.3%(37/55)和63.6%(35/55) (表 3)。

| (耐药菌株数/菌株数) | |||

| 抗生素类别 | 抗生素 | MRSA耐药率 | MSSA耐药率 |

| β-内酰胺类 | 苯唑西林(OXA) | 90.3(28/31) | 0 |

| 青霉素(PEN) | 100(31/31) | 89.1(49/55) | |

| 氨基糖苷类 | 庆大霉素(GEN) | 87.1(27/31) | 5.5(3/55) |

| 糖肽类 | 万古霉素(VAN) | 0 | 0 |

| 替考拉宁(TEC) | 0 | 0 | |

| 利福霉素类 | 利福平(RIF) | 83.9(26/31) | 0 |

| 四环素类 | 四环素(TET) | 87.1(27/31) | 12.7(7/55) |

| 喹诺酮类 | 环丙沙星(CIP) | 87.1(27/31) | 5.5(3/55) |

| 左氧佛沙星(LEV) | 83.9(26/31) | 1.8(1/55) | |

| 林可胺类 | 克林霉素(CLI) | 71.0(22/31) | 63.6(35/55) |

| 大环内酯类 | 红霉素(ERY) | 74.2(23/31) | 67.3(37/55) |

| 磺胺类 | 复方新诺明(SXT) | 6.5(2/31) | 18.2(10/55) |

| 唑烷酮类 | 利奈唑胺(LZD) | 3.2(1/31) | 0 |

所有的MRSA菌株均为MDR菌株,而55株MSSA菌株中有31株为MDR菌株。22株ST239 MRSA菌株有共同的耐药谱PEN/CIP/GEN/RIF/TET/LEV(表 3)。31株MSSA多重耐药菌株中,有23 株对三类抗生素耐药,并且耐药谱都为PEN/ERY/CLI(表 4),相应的31株MDR菌株青霉素、红霉素、克林霉素耐药基因检出率分别为blaZ(100%,31/31),ermC(96.8%,30/31),ermA(12.9%,4/31),另外有8株 MSSA对四类以上的抗生素耐药。10株ST121菌株中有8株为MDR菌株;4株ST398菌株中有2株对四类以上抗生素耐药,其中1株对6类抗生素耐药(PEN/ERY/CLI/SXT/CIP/TET),并且对左氧佛沙星和庆大霉素中介耐药。在19株PFGE聚类组F型菌株中有16株为MDR菌株,远高于其他聚类组。

| (括号内数字为菌株数) | |||||

| 耐药谱 (菌株数) | MLST型别 (菌株数) | spa型别 (菌株数) | agr型别 (菌株数) | PFGE型别 (菌株数) | pvl+ 菌株数 |

| PEN/ERY/CLI(23) | ST121(7) | t284(3),t030(1),t159(1),t435(1),t850(1) | Ⅳ(6),Ⅰ(1) | F(7) | 6 |

| ST22(6) | t11413(4),t284(1),new(1) | Ⅰ(6) | A(1),B(1),F(3),J(1) | 5 | |

| ST15(2) | t571(1),t11518(1) | Ⅱ(2) | B(1),F(1) | 0 | |

| ST88(2) | t2592(2) | Ⅲ(2) | C(1),J(1) | 2 | |

| ST217(2) | t571(1),t11413(1) | Ⅰ(2) | F(2) | 0 | |

| ST1(1) | t127(1) | Ⅲ(1) | A(1) | 1 | |

| ST5(1) | t002(1) | Ⅱ(1) | A(1) | 1 | |

| ST630(1) | t377(1) | Ⅰ(1) | B(1) | 0 | |

| ST943(1) | t2617(1) | Ⅰ(1) | F(1) | 0 | |

| PEN/ERY/CLI/SXT(3) | ST88(1),ST59(1),ST398(1) | t163(1),t2592(1),t2876(1) | Ⅰ(2),Ⅲ(1) | B(1),E(1) | 1 |

| PEN/ERY/CLI/TET(2) | ST30(1),ST121(1) | t030(1),t1130(1) | Ⅰ(1),Ⅲ(1) | F(2) | 2 |

| PEN/ERY/CLI/CIP(1) | ST630(1) | t377(1) | Ⅰ(1) | B(1) | 0 |

| PEN/ERY/CLI/SXT/GEN(1) | ST1920(1) | t5356(1) | Ⅲ(1) | C(1) | 0 |

| PEN/ERY/CLI/SXT/CIP/TET(1) | ST398(1) | t030(1) | Ⅰ(1) | 未分型 | 0 |

| PEN:青霉素;ERY:红霉素;CLI:克林霉素;SXT:复方新诺明;CIP:环丙沙星;TET:四环素 | |||||

自20世纪80年代开始,MRSA因其具有较强的外界环境适应能力和定植能力,以及对抗生素的耐受能力,在全球范围内迅速传播,成为医院和社区感染的重要病原菌。在我国,临床金葡菌中的MRSA检出率从1980年的20%迅速升高到2008年的约60%[31],且不同地区存在较大差异,引起了国内科技工作者的高度关注。近年来的研究发现ST239-MRSA-Ⅲ-t030/t037、ST5-MRSA-Ⅱ-t002是我国MRSA优势流行型 别[7, 8]。本研究中,来自乌鲁木齐地区的MRSA检出率为36%(31/86),低于全国平均水平,该地区的MRSA 优势流行型别为ST239-MRSA-Ⅲ-t030 (71%,22/31),这些结果与文献[32]报道的对乌鲁木齐地区MRSA研究结果相一致。ST239-MRSA-Ⅲ源于Brazili/Hungarian克隆株,首先发现于巴西[33],随后蔓延到邻近的南美和欧洲一些国家,并很快取代了当地流行克隆成为优势克隆,ST239也是大部分亚洲国家的主要流行克隆[34]。在2000年之前,ST239-t037是我国的主要克隆,但是后来逐渐被ST239-t030取代[35],本研究中ST239-t030仍然是最优势克隆,未检出ST239-t037菌株,这可能是因为ST239-t030型菌株在乌鲁木齐地区有更强的适应能力和传播能力。药敏试验结果表明,ST239-MRSA-Ⅲ型金葡菌有共同的耐药谱OXA/PEN/CIP/GEN/RIF/TET/LEV,对红霉素、克林霉素也表现出较高程度的耐药。

相对于MRSA而言,MSSA菌株拥有更高的遗传多样性[36],在我国的研究报道中,主要的MSSA型别因地区不同而差异较大[35, 37]。本研究中55株MSSA 菌株可分为16种ST型别和23种spa型,相对于MRSA 菌株(6种ST型别,8种spa型)来看,MSSA具有更多的克隆多态性。t11413、t571、t030、t2592、t284和t002是主要的spa型别,而ST22、ST121、ST88、ST15、ST398和ST1920是主要的MLST型别。其中t11413、ST121在以前我国的研究中鲜有报道,可能是在乌鲁木齐地区新流行的克隆。t571型MSSA一般与ST398相关联,是欧洲及我国牲畜来源的主要流行克隆群,常引起皮肤和软组织感染[38]。t2592型MSSA主要在我国东北地区流行[39],本研究中有5株此型菌株检出,成为乌鲁木齐地区主要克隆群,并且都为ST88-agr Ⅲ型。ST121是在全球广泛分布的社区获得性克隆群,因其高毒力而引起研究者关注[40]。我国对于ST121金葡菌的报道较少,在本研究中,有10株MSSA菌株检测为ST121型(18.2%,10/55),成为主要流行克隆群,并且有8株携带pvl毒力基因(80.0%,8/10),高pvl携带率可能是ST121型MSSA具有高毒力的重要因素之一。

agr系统位于金葡菌基因组的核心区域,因此一般与菌株的MLST型别相关联。本研究中发现,agrⅠ为MSSA主要型别,并且与ST22、ST398型别相关;agrⅡ型与ST15、ST5型相对应;agrⅢ主要为ST88型;8株 agr Ⅳ型菌株都为ST121型,这些结果与文献[38, 41]报道相一致。本研究还发现MSSA的pvl携带率(49.1%)高于MRSA(38.7%)菌株,尤其以MSSA菌株ST22(83.3%,10/12)和ST121(80%,8/10)的pvl阳性率为突出,提示在乌鲁木齐地区应重点加强对这些菌株所致临床感染的防控。

在欧美地区,临床分离的MSSA对除青霉素之外的大多数常用抗生素敏感[36, 42],因此MSSA的耐药情况并未引起足够重视。在我国的报道中,已发现MSSA除对青霉素耐药外,还对红霉素、克林霉素等存在不同程度的耐药[39]。在本研究的55株MSSA菌株中检出了高比例的多重耐药菌株(56.4%,31/55),这些MDR菌有共同的耐药谱PEN/ERY/CLI。31株MDR中有23株对三类抗生素耐药,6株对四类抗生素耐药,1株耐五类抗生素,另外有1株菌株对六类抗生 素耐药,提示MSSA的耐药性在乌鲁木齐地区不容乐观。MSSA菌株对复方新诺明的耐药率(18.2%,10/55)高于MRSA菌株(6.5%,2/31);10株ST121型菌株有7株(均为pvl阳性)为多重耐药菌株,此型菌株在乌鲁木齐地区的流行可能与其高毒力、多重耐药相关。

综上所述,本研究在一定程度上揭示了乌鲁木齐地区MRSA和MSSA的种群分子特征及耐药情况,其中MRSA以ST239-MRSA-Ⅲ-t030占绝对优势;而MSSA分子型别则呈现出多样性,ST121、ST22成为该地区的优势克隆,并且表现出高毒力、高耐药性。罕见报道的spa型别t11413在本研究的MSSA中检出比例最高,对于其来源还需进一步研究。我们的研究提示,在我国金葡菌感染的防控中,除关注MRSA外,MSSA以其较高的毒力以及越来越严峻的耐药形势同样需要给予高度重视。

| [1] | Lowy F D. Staphylococcus aureus infections[J]. N Engl J Med, 1998, 339(8): 520-532. DOI: 10.1056/NEJM199808203390806 |

| [2] | Robinson D A, Enright M C. Evolutionary models of the emergence of methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus[J]. Antimicrob Agents Chemother, 2003, 47(12): 3926-3934. |

| [3] | Stefani S, Chung D R, Lindsay J A, et al. Meticillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA): global epidemiology and harmonisation of typing methods[J]. Int J Antimicrob Agents, 2012, 39(4): 273-282. DOI: 10.1016/j.ijantimicag.2011.09.030 |

| [4] | Deurenberg R H, Stobberingh E E. The evolution of Staphylococcus aureus[J]. Infect Genet Evol, 2008, 8(6): 747-763. DOI: 10.1016/j.meegid.2008.07.007 |

| [5] | Enright M C, Robinson D A, Randle G, et al. The evolutionary history of methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA)[J]. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA, 2002, 99(11): 7687-7692. DOI: 10.1073/pnas.122108599 |

| [6] | Chambers H F, Deleo F R. Waves of resistance: Staphylococcus aureus in the antibiotic era[J]. Nat Rev Microbiol, 2009, 7(9): 629-641. DOI: 10.1038/nrmicro2200 |

| [7] | Cheng H, Yuan W, Zeng F, et al. Molecular and phenotypic evidence for the spread of three major methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus clones associated with two characteristic antimicrobial resistance profiles in China[J]. J Antimicrob Chemother, 2013, 68(11): 2453-2457. DOI: 10.1093/jac/dkt213 |

| [8] | Liu Y, Wang H, Du N, et al. Molecular evidence for spread of two major methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus clones with a unique geographic distribution in Chinese hospitals[J]. Antimicrob Agents Chemother, 2009, 53(2): 512-518. DOI: 10.1128/AAC.00804-08 |

| [9] | Grundmann H, Aanensen D M, van-den-Wijngaard C C, et al. Geographic distribution of Staphylococcus aureus causing invasive infections in Europe: a molecular-epidemiological analysis[J]. PLoS Med, 2010, 7(1): e1000215. DOI: 10.1371/journal.pmed.1000215 |

| [10] | Liu M, Liu J, Guo Y, et al. Characterization of virulence factors and genetic background of Staphylococcus aureus isolated from Peking University People’s Hospital between 2005 and 2009[J]. Curr Microbiol, 2010, 61(5): 435-443. DOI: 10.1007/s00284-010-9635-0 |

| [11] | David M Z, Boyle-Vavra S, Zychowski D L, et al. Methicillin-susceptible Staphylococcus aureus as a predominantly healthcare-associated pathogen: a possible reversal of roles?[J]. PLoS One, 2011, 6(4): e18217. DOI: 10.1371/journal.pone.0018217 |

| [12] | Yoong P, Torres V J. The effects of Staphylococcus aureus leukotoxins on the host: cell lysis and beyond[J]. Curr Opin Microbiol, 2013, 16(1): 63-69. DOI: 10.1016/j.mib.2013.01.012 |

| [13] | Goering R V, Shawar R M, Scangarella N E, et al. Molecular epidemiology of methicillin-resistant and methicillin-susceptible Staphylococcus aureus isolates from global clinical trials[J]. J Clin Microbiol, 2008, 46(9): 2842-2847. DOI: 10.1128/JCM.00521-08 |

| [14] | Sawanobori E, Hung W C, Takano T, et al. Emergence of Panton-Valentine leukocidin-positive ST59 methicillin-susceptible Staphylococcus aureus with high cytolytic peptide expression in association with community-acquired pediatric osteomyelitis complicated by pulmonary embolism[J]. J Microbiol Immunol Infect, 2015, 48(5): 565-573. DOI: 10.1016/j.jmii.2014.04.015 |

| [15] | Enright M C, Day N P, Davies C E, et al. Multilocus sequence typing for characterization of methicillin-resistant and methicillin-susceptible clones of Staphylococcus aureus[J]. J Clin Microbiol, 2000, 38(3): 1008-1015. |

| [16] | Oliveira D C, Milheirico C, de-Lencastre H. Redefining a structural variant of staphylococcal cassette chromosome mec, SCCmec type Ⅵ[J]. Antimicrob Agents Chemother, 2006, 50(10): 3457-3459. DOI: 10.1128/AAC.00629-06 |

| [17] | Koreen L, Ramaswamy S V, Graviss E A, et al. spa typing method for discriminating among Staphylococcus aureus isolates: implications for use of a single marker to detect genetic micro- and macrovariation[J]. J Clin Microbiol, 2004, 42(2): 792-799. |

| [18] | 程航, 曾方银, 胡启文, 等. 广州地区耐甲氧西林金黄色葡萄球菌的分子分型及耐药性分析[J]. 第三军医大学学报, 2013, 35(8): 696-701. |

| [19] | Gilot P, Lina G, Cochard T, et al. Analysis of the genetic variability of genes encoding the RNA Ⅲ-activating components Agr and TRAP in a population of Staphylococcus aureus strains isolated from cows with mastitis[J]. J Clin Microbiol, 2002, 40(11): 4060-4067. |

| [20] | Lee S, Kwon K T, Kim H I, et al. Clinical implications of cefazolin inoculum effect and β-lactamase type on methicillin-susceptible Staphylococcus aureus bacteremia[J]. Microb Drug Resist, 2014, 20(6): 568-574. DOI: 10.1089/mdr.2013.0229 |

| [21] | Reischl U, Tuohy M J, Hall G S, et al. Rapid detection of Panton-Valentine leukocidin-positive Staphylococcus aureus by real-time PCR targeting the lukS-PV gene[J]. Eur J Clin Microbiol Infect Dis, 2007, 26(2): 131-135. DOI: 10.1007/s10096-007-0254-z |

| [22] | Strommenger B, Kettlitz C, Werner G, et al. Multiplex PCR assay for simultaneous detection of nine clinically relevant antibiotic resistance genes in Staphylococcus aureus[J]. J Clin Microbiol, 2003, 41(9): 4089-4094. |

| [23] | Unal S, Hoskins J, Flokowitsch J E, et al. Detection of methicillin-resistant staphylococci by using the polymerase chain reaction[J]. J Clin Microbiol, 1992, 30(7): 1685-1691. |

| [24] | Kobayashi N, Wu H, Kojima K, et al. Detection of mecA, femA, and femB genes in clinical strains of staphylococci using polymerase chain reaction[J]. Epidemiol Infect, 1994, 113(2): 259-266. |

| [25] | Harmsen D, Claus H, Witte W, et al. Typing of methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus in a university hospital setting by using novel software for spa repeat determination and database management[J]. J Clin Microbiol, 2003, 41(12): 5442-5448. |

| [26] | Ruppitsch W, Indra A, Stoger A, et al. Classifying spa types in complexes improves interpretation of typing results for methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus[J]. J Clin Microbiol, 2006, 44(7): 2442-2448. DOI: 10.1128/JCM.00113-06 |

| [27] | Bannerman T L, Hancock G A, Tenover F C, et al. Pulsed-field gel electrophoresis as a replacement for bacteriophage typing of Staphylococcus aureus[J]. J Clin Microbiol, 1995, 33(3): 551-555. |

| [28] | Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute. Performance Standards for Antimicrobial Susceptibility Testing: Twenty-First Informational Supplement. CLSI Document M100-S21[M]. Wayne: Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute, 2011. |

| [29] | Magiorakos A P, Srinivasan A, Carey R B, et al. Multidrug-resistant, extensively drug-resistant and pandrug-resistant bacteria: an international expert proposal for interim standard definitions for acquired resistance[J]. Clin Microbiol Infect, 2012, 18(3): 268-281. DOI: 10.1111/j.1469-0691.2011.03570.x |

| [30] | Li G, Wu C, Wang X, et al. Prevalence and characterization of methicillin susceptible Staphylococcus aureus ST398 isolates from retail foods[J]. Int J Food Microbiol, 2015, 196: 94-97. DOI: 10.1016/j.ijfoodmicro.2014.12.002 |

| [31] | Xiao Y H, Giske C G, Wei Z Q, et al. Epidemiology and characteristics of antimicrobial resistance in China[J]. Drug Resist Updat, 2011, 14(4/5): 236-250. DOI: 10.1016/j.drup.2011.07.001 |

| [32] | Chen Y, Liu Z, Duo L, et al. Characterization of Staphylococcus aureus from distinct geographic locations in China: an increasing prevalence of spa-t030 and SCCmec type Ⅲ[J]. PLoS One, 2014, 9(4): e96255. DOI: 10.1371/journal.pone.0096255 |

| [33] | Teixeira L A, Resende C A, Ormonde L R, et al. Geographic spread of epidemic multiresistant Staphylococcus aureus clone in Brazil[J]. J Clin Microbiol, 1995, 33(9): 2400-2404. |

| [34] | Feil E J, Nickerson E K, Chantratita N, et al. Rapid detection of the pandemic methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus clone ST 239, a dominant strain in Asian hospitals[J]. J Clin Microbiol, 2008, 46(4): 1520-1522. DOI: 10.1128/JCM.02238-07 |

| [35] | Chen H, Liu Y, Jiang X, et al. Rapid change of methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus clones in a Chinese tertiary care hospital over a 15-year period[J]. Antimicrob Agents Chemother, 2010, 54(5): 1842-1847. DOI: 10.1128/AAC.01563-09 |

| [36] | Miko B A, Hafer C A, Lee C J, et al. Molecular characterization of methicillin-susceptible Staphylococcus aureus clinical isolates in the United States, 2004 to 2010[J]. J Clin Microbiol, 2013, 51(3): 874-879. DOI: 10.1128/JCM.00923-12 |

| [37] | Liu C, Chen Z J, Sun Z, et al. Molecular characteristics and virulence factors in methicillin-susceptible, resistant, and heterogeneous vancomycin-intermediate Staphylococcus aureus from central-southern China[J]. J Microbiol Immunol Infect, 2015, 48(5): 490-496. DOI: 10.1016/j.jmii.2014.03.003 |

| [38] | Zhao C, Liu Y, Zhao M, et al. Characterization of community acquired Staphylococcus aureus associated with skin and soft tissue infection in Beijing: high prevalence of PVL+ ST398[J]. PLoS One, 2012, 7(6): e38577. DOI: 10.1371/journal.pone.0038577 |

| [39] | Sun D D, Ma X X, Hu J, et al. Epidemiological and molecular characterization of community and hospital acquired Staphylococcus aureus strains prevailing in Shenyang, Northeastern China[J]. Braz J Infect Dis, 2013, 17(6): 682-690. DOI: 10.1016/j.bjid.2013.02.007 |

| [40] | Rao Q, Shang W, Hu X, et al. Staphylococcus aureus ST121: a globally disseminated hypervirulent clone[J]. J Med Microbiol, 2015, 64(12): 1462-1473. DOI: 10.1099/jmm.0.000185 |

| [41] | Holtfreter S, Grumann D, Schmudde M, et al. Clonal distribution of superantigen genes in clinical Staphylococcus aureus isolates[J]. J Clin Microbiol, 2007, 45(8): 2669-2680. DOI: 10.1128/JCM.00204-07 |

| [42] | Rasmussen G, Monecke S, Brus O, et al. Long term molecular epidemiology of methicillin-susceptible Staphylococcus aureus bacteremia isolates in Sweden[J]. PLoS One, 2014, 9(12): e114276. DOI: 10.1371/journal.pone.0114276 |